ఇరాక్: కూర్పుల మధ్య తేడాలు

| పంక్తి 78: | పంక్తి 78: | ||

<ref name="ʿERĀQ-EʿAJAMĪ Persian Iraq">{{cite web |title=ʿERĀQ-E ʿAJAM(Ī) |url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/eraq-e-ajami |publisher=Encyclopaedia Iranica}}</ref><ref name="Bernhardsson-97">{{cite book|author=Magnus Thorkell Bernhardsson|title=Reclaiming a Plundered Past: Archaeology And Nation Building in Modern Iraq|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MVHtRZwU-cAC&pg=PA97|year=2005|publisher=University of Texas Press|isbn=978-0-292-70947-8|page=97|quote=The term Iraq did not encompass the regions north of the region of Tikrit on the Tigris and near Hīt on the Euphrates.}}</ref> |

<ref name="ʿERĀQ-EʿAJAMĪ Persian Iraq">{{cite web |title=ʿERĀQ-E ʿAJAM(Ī) |url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/eraq-e-ajami |publisher=Encyclopaedia Iranica}}</ref><ref name="Bernhardsson-97">{{cite book|author=Magnus Thorkell Bernhardsson|title=Reclaiming a Plundered Past: Archaeology And Nation Building in Modern Iraq|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MVHtRZwU-cAC&pg=PA97|year=2005|publisher=University of Texas Press|isbn=978-0-292-70947-8|page=97|quote=The term Iraq did not encompass the regions north of the region of Tikrit on the Tigris and near Hīt on the Euphrates.}}</ref> |

||

ప్రారంభ ఇస్లామిక్ వాడుకలో సారవంతమైన భూమిని (టిగ్రిస్ మరియు యూఫ్రేట్స్ సారవంతమైన భూమిని ) సవాద్ అంటారు. అరబిక్ పదం {{lang|ar|عراق}} అంటే అంచు, తీరం మరియు కొన అని అర్ధం. గ్రామీణ భాషలో ఏటవాలు ప్రాంతం అని అర్ధం. అల్- జజిరా (మెసపటోమియా) మైదానం అల్- ఇరాక్ అరబి ఉత్తర పశ్చిమ తీరంలో ఉంది. <ref>{{cite journal|last=Boesch|first=Hans H.|title=El-'Iraq|journal=Economic Geography|date=1 October 1939|volume=15|issue=4|page=329|doi=10.2307/141771}}</ref>. |

ప్రారంభ ఇస్లామిక్ వాడుకలో సారవంతమైన భూమిని (టిగ్రిస్ మరియు యూఫ్రేట్స్ సారవంతమైన భూమిని ) సవాద్ అంటారు. అరబిక్ పదం {{lang|ar|عراق}} అంటే అంచు, తీరం మరియు కొన అని అర్ధం. గ్రామీణ భాషలో ఏటవాలు ప్రాంతం అని అర్ధం. అల్- జజిరా (మెసపటోమియా) మైదానం అల్- ఇరాక్ అరబి ఉత్తర పశ్చిమ తీరంలో ఉంది. <ref>{{cite journal|last=Boesch|first=Hans H.|title=El-'Iraq|journal=Economic Geography|date=1 October 1939|volume=15|issue=4|page=329|doi=10.2307/141771}}</ref>. |

||

==History== |

|||

{{main|History of Iraq}} |

|||

===Pre-historic era=== |

|||

Between 65,000 BC and 35,000 BC northern Iraq was home to a [[Neanderthal]] culture, archaeological remains of which have been discovered at [[Shanidar Cave]]<ref>Edwards, Owen (March 2010). "The Skeletons of Shanidar Cave". Smithsonian. Retrieved 17 October 2014.</ref> |

|||

This same region is also the location of a number of pre-Neolithic cemeteries, dating from approximately 11,000 BC.<ref name="Ralph S. Solecki 2004 pp. 3">Ralph S. Solecki, Rose L. Solecki, and Anagnostis P. Agelarakis (2004). The Proto-Neolithic Cemetery in Shanidar Cave. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN 9781585442720.</ref> |

|||

Since approximately 10,000 BC, Iraq (alongside [[Asia Minor]] and [[The Levant]]) was one of centres of a [[Caucasoid]] [[Neolithic]] culture (known as [[Pre-Pottery Neolithic A]]) where agriculture and cattle breeding appeared for the first time in the world. The following Neolithic period ([[PPNB]]) is represented by rectangular houses. At the time of the pre-pottery Neolithic, people used vessels made of stone, gypsum and burnt lime (Vaisselle blanche). Finds of obsidian tools from Anatolia are evidences of early trade relations. |

|||

Further important sites of human advancement were [[Jarmo]] (circa 7100 BC),<ref name="Ralph S. Solecki 2004 pp. 3"/> the [[Halaf culture]] and [[Ubaid period]] (between 6500 BC and 3800 BC),<ref>Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and Integration in the Late Prehistoric Societies of the Middle East (Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization, Number 63) The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (2010) ISBN 978-1-885923-66-0 p.2, at http://oi.uchicago.edu/research/pubs/catalog/saoc/saoc63.html; "Radiometric data suggest that the whole Southern Mesopotamian Ubaid period, including Ubaid 0 and 5, is of immense duration, spanning nearly three millennia from about 6500 to 3800 B.C".</ref> these periods show ever increasing levels of advancement in agriculture, tool making and architecture. |

|||

===Ancient Iraq=== |

|||

{{one source|section|date=June 2014}} |

|||

[[File:Cylinder Seal, Old Babylonian, formerly in the Charterhouse Collection 09.jpg|thumb|320px|right|[[Cylinder Seal]], Old Babylonian Period, c.1800 BCE, [[hematite]]. The king makes an animal offering to [[Shamash]]. This seal was probably made in a workshop at [[Sippar]].<ref>Al-Gailani Werr, L., 1988. Studies in the chronology and regional style of Old Babylonian Cylinder Seals. Bibliotheca Mesopotamica, Volume 23.</ref> ]] |

|||

{{main|History of Mesopotamia}} |

|||

The historical period in Iraq truly begins during the [[Uruk period]] (4000 BC to 3100 BC), with the founding of a number of [[Sumer]]ian [[cities]], and the use of [[Pictographs]], [[Cylinder seals]] and mass-produced goods.<ref>Crawford 2004, p. 75</ref> |

|||

The "[[Cradle of Civilization]]" is thus a common term for the area comprising modern Iraq as it was home to the earliest known [[civilisation]], the [[Sumerian civilisation]], which arose in the fertile [[Tigris-Euphrates river system|Tigris-Euphrates river valley]] of southern Iraq in the [[Chalcolithic]] ([[Ubaid period]]). |

|||

It was here in the late [[4th millennium BC]], that the world's [[List of languages by first written accounts|first]] [[Cuneiform script|writing system]] and recorded history itself were born. The [[Sumerians]] were also the first to harness the [[wheel]] and create [[City States]], and whose writings record the first evidence of [[Mathematics]], [[Astronomy]], [[Astrology]], [[Written Law]], [[Medicine]] and [[Organised religion]]. |

|||

The Sumerians spoke a [[Language Isolate]], in other words, a language utterly unrelated to any other, including the [[Semitic Languages]], [[Indo-European Languages]], [[Afroasiatic languages]] or any other isolates. The major city states of the early Sumerian period were; [[Eridu]], [[Bad-tibira]], [[Larsa]], [[Sippar]], [[Shuruppak]], [[Uruk]], [[Kish (Sumer)|Kish]], [[Ur]], [[Nippur]], [[Lagash]], [[Girsu]], [[Umma]], [[Hamazi]], [[Adab (city)|Adab]], [[Mari, Syria|Mari]], [[Isin]], [[Kutha]], [[Der (Sumer)|Der]] and [[Akshak]]. |

|||

Cities such as [[Ashur]], [[Arbil|Arbela]] (modern [[Irbil]]) and [[Arrapkha]] (modern [[Kirkuk]]) were also extant in what was to be called Assyria from the 25th century BC, however at this early stage they were Sumerian ruled administrative centres. |

|||

[[File:P1150890 Louvre stèle de victoire Akkad AO2678 rwk.jpg|thumb|Victory stele of [[Naram-Sin of Akkad]].]] |

|||

In the 26th century BC, [[Eannatum]] of [[Lagash]] created what was perhaps the first [[Empire]] in history, though this was short lived. Later, [[Lugal-Zage-Si]], the priest-king of [[Umma]], overthrew the primacy of the Lagash dynasty in the area, then conquered [[Uruk]], making it his capital, and claimed an empire extending from the [[Persian Gulf]] to the [[Mediterranean]].<ref>Roux, Georges (1993), "Ancient Iraq" (Penguin)</ref> It was during this period that the [[Epic of Gilgamesh]] originates, which includes the tale of [[The Great Flood]]. |

|||

From approximately 3000 BC, a [[Semitic people]] had also entered Iraq from the west and settled amongst the Sumerians. These people spoke an [[East Semitic language]] which would later come to be known as [[Akkadian language|Akkadian]]. From the 29th century BC Akkadian Semitic names began to appear on king lists and administrative documents of various city states. |

|||

During the 3rd millennium BCE a cultural symbiosis developed between the Sumerians and the Akkadians, which included widespread [[bilingualism]]. The influences between [[Sumer]]ian and [[Akkadian]] are evident in all areas including lexical borrowing on a massive scale—and syntactic, morphological, and phonological convergence. This mutual influence has prompted scholars to refer to Sumerian and Akkadian of the 3rd millennium BCE as a [[Sprachbund]].<ref>Deutscher, Guy (2007). Syntactic Change in Akkadian: The Evolution of Sentential Complementation. Oxford University Press US. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-19-953222-3.</ref> From this period the civilisation in Iraq came to be known as [[Sumero-Akkadian]]. |

|||

[[File:Bill of sale Louvre AO3765.jpg|thumb|180px|Bill of sale of a male slave and a building in [[Shuruppak]], Sumerian tablet, circa 2600 BCE.]] |

|||

Between the 29th and 24th centuries BC, a number of kingdoms and city states within Iraq began to have Akkadian speaking dynasties; including [[Assyria]], [[Ekallatum]], [[Isin]] and [[Larsa]]. |

|||

However, the Sumerians remained generally dominant until the rise of the [[Akkadian Empire]] (2335-2124 BC), based in the city of [[Akkad (city)|Akkad]] in central Iraq. [[Sargon of Akkad]], originally a [[Rabshakeh]] to a Sumerian king, founded the empire, he conquered all of the city states of southern and central Iraq, and subjugated the kings of Assyria, thus uniting the Sumerians and Akkadians in one state. He then set about expanding his empire, conquering [[Gutium]], [[Elam]], [[Cissia (area)|Cissia]] and [[Turukku]] in [[Ancient Iran]], the [[Hurrians]], [[Luwians]] and [[Hattians]] of [[Anatolia]], and the [[Amorites]] and [[Ebla]]ites of [[Ancient Syria]]. |

|||

After the collapse of the Akkadian Empire in the late 22nd century BC, the [[Gutians]] occupied the south for a few decades, while Assyria reasserted its independence in the north. This was followed by a Sumerian renaissance in the form of the [[Neo-Sumerian Empire]]. The Sumerians under king [[Shulgi]] conquered almost all of Iraq except the northern reaches of Assyria, and asserted themselves over the [[Elamites]], [[Gutians]] and [[Amorites]]. |

|||

An [[Elam]]ite invasion in 2004 BC brought the Sumerian revival to an end. By the mid 21st century BC the Akkadian speaking kingdom of [[Assyria]], had risen to dominance in northern Iraq, it expanded territorially into the north eastern Levant, central Iraq, and eastern Anatolia, forming the [[Old Assyrian Empire]] (circa 2035-1750 BC) under kings such as [[Puzur-Ashur I]], [[Sargon I]], [[Ilushuma]] and [[Erishum I]], the latter of whom produced the most detailed set of [[Written Laws]] yet written. The south broke up into a number of Akkadian speaking states, [[Isin]], [[Larsa]] and [[Eshnunna]] being the major ones. |

|||

During the 20th century BC, the [[Canaanite language|Canaanite]] speaking [[Northwest Semitic]] [[Amorites]] began to migrate into southern Mesopotamia. Eventually these Amorites began to set up small petty kingdoms in the south, as well as usurping the thrones of extant city states such as [[Isin]], [[Larsa]] and [[Eshnunna]]. |

|||

[[File:P1050771 Louvre code Hammurabi bas relief rwk.JPG|thumb|180px|[[Hammurabi]], depicted as receiving his royal insignia from [[Shamash]]. Relief on the upper part of the stele of [[code of Hammurabi|Hammurabi's code of laws]].]] |

|||

One of these small kingdoms founded in 1894 BC contained the then small administrative town of [[Babylon]] within its borders. It remained insignificant for over a century, overshadowed by older and more powerful states such as Assyria, Elam, Isin, Ehnunna and Larsa. |

|||

In 1792 BC, an [[Amorite]] ruler named [[Hammurabi]] came to power in this state, and immediately set about building Babylon from a minor town into a major city, declaring himself its king. Hammurabi conquered the whole of southern and central Iraq, as well as Elam to the east and Mari to the west, then engaged in a protracted war with the Assyrian king [[Ishme-Dagan]] for domination of the region, creating the short lived [[Babylonian Empire]]. He eventually prevailed over the successor of Ishme-Dagan and subjected Assyria and its Anatolian colonies. |

|||

It is from the period of Hammurabi that southern Iraq came to be known as [[Babylonia]], while the north had already coalesced into [[Assyria]] hundreds of years before. However, his empire was short lived, and rapidly collapsed after his death, with both Assyria and southern Iraq, in the form of the [[Sealand Dynasty]], falling back into native Akkadian hands. The foreign Amorites clung on to power in a once more weak and small Babylonia until it was sacked by the [[Indo-European]] speaking [[Hittite Empire]] based in [[Anatolia]] in 1595 BC. After this, another foreign people, the [[Language Isolate]] speaking [[Kassites]], originating in the [[Zagros Mountains]] of [[Ancient Iran]], seized control of Babylonia, where they were to rule for almost six hundred years, by far the longest dynasty ever to rule in Babylon. |

|||

Iraq was from this point divided into three polities; [[Assyria]] in the north, [[Kassite]] [[Babylonia]] in the south central region, and the [[Sealand Dynasty]] in the far south. The Sealand Dynasty was finally conquered into Babylonia by the Kassites circa 1380 BC. |

|||

The [[Middle Assyrian Empire]] (1365–1020 BC) saw Assyria rise to be the most powerful nation in the known world. Beginning with the campaigns of [[Ashur-uballit I]], Assyria destroyed the rival [[Hurrian]]-[[Mitanni]] Empire, annexed huge swathes of the [[Hittite Empire]] for itself, annexed northern Babylonia from the Kassites, forced the [[Egyptian Empire]] from the region, and defeated the [[Elamites]], [[Phrygians]], [[Canaanites]], [[Phoenicians]], [[Cilicians]], [[Gutians]], [[Dilmun]]ites and [[Arameans]]. At its height the [[Middle Assyrian Empire]] stretched from [[The Caucasus]] to [[Dilmun]] (modern [[Bahrain]]), and from the [[Mediterranean]] coasts of [[Phoenicia]] to the [[Zagros Mountains]] of [[Iran]]. In 1235 BC, [[Tukulti-Ninurta I]] of Assyria took the throne of [[Babylon]], thus becoming the very first ''native Mesopotamian'' to rule the state. |

|||

[[File:Jehu-Obelisk-cropped.jpg|thumb|[[Jehu]], king of [[Kingdom of Israel (Samaria)|Israel]], bows before Shalmaneser III of [[Assyria]], 825 BC.]] |

|||

During the [[Bronze Age collapse]] (1200-900 BC) Babylonia was in a state of chaos, dominated for long periods by Assyria and [[Elam]]. The Kassites were driven from power by Assyria and Elam, allowing native south Mesopotamian kings to rule Babylonia for the first time, although often subject to Assyrian or Elamite rulers. However, these [[East Semitic languages|East Semitic]] Akkadian kings, were unable to prevent new waves of [[West Semitic languages|West Semitic]] migrants entering southern Iraq, and during the 11th century BC [[Arameans]] and [[Suteans]] entered Babylonia from [[The Levant]], and these were followed in the late 10th to early 9th century BC by the migrant [[Chaldea]]ns who were closely related to the earlier [[Arameans]]. |

|||

After a period of comparative decline in Assyria, it once more began to expand with the [[Neo Assyrian Empire]] (935–605 BC). This was to be the largest and most powerful empire the world had yet seen, and under rulers such as [[Adad-Nirari II]], [[Ashurnasirpal I|Ashurnasirpal]], [[Shalmaneser III]], [[Semiramis]], [[Tiglath-pileser III]], [[Sargon II]], [[Sennacherib]], [[Esarhaddon]] and [[Ashurbanipal]], Iraq became the centre of an empire stretching from [[Persia]], [[Parthia]] and [[Elam]] in the east, to [[Cyprus]] and [[Antioch]] in the west, and from [[The Caucasus]] in the north to [[Egypt]], [[Nubia]] and [[Arabia]] in the south. |

|||

The [[Arab people|Arabs]] are first mentioned in written history (circa 850 BC) as a subject people of [[Shalmaneser III]], dwelling in the Arabian Peninsula. The [[Chaldea]]ns are first mentioned at this time also. |

|||

It was during this period that an Akkadian influenced form of [[Eastern Aramaic]] was introduced by the Assyrians as the [[lingua franca]] of their vast empire, and Mesopotamian Aramaic began to supplant Akkadian as the spoken language of the general populace of both Assyria and Babylonia. The descendant dialects of this tongue survive amongst the [[Assyrian people|Assyrians]] of northern Iraq to this day. |

|||

[[File:Loewenjagd -645-635 Niniveh.JPG|thumb|Relief showing a [[Lion hunting|lion hunt]], from the north palace of [[Nineveh]], 645-635 BC.]] |

|||

In the late 7th century BC the Assyrian Empire tore itself apart with a series of brutal civil wars, weakening itself to such a degree that a coalition of its former subjects; the [[Babylonians]], [[Chaldea]]ns, [[Medes]], [[Persian people|Persians]], [[Parthians]], [[Scythians]] and [[Cimmerians]], were able to attack Assyria, finally bringing its empire down by 605 BC.<ref>Georges Roux - Ancient Iraq</ref> |

|||

The short lived [[Neo-Babylonian Empire]] (620-539 BC) succeeded that of Assyria. It failed to attain the size, power or longevity of its predecessor, however it came to dominate [[The Levant]], [[Canaan]], [[Arabia]], [[Kingdom of Israel (Samaria)|Israel]] and [[Kingdom of Judah|Judah]], and to defeat [[Egypt]]. Initially, Babylon was ruled by yet another foreign dynasty, that of the [[Chaldea]]ns, who had migrated to the region in the late 10th or early 9th century BC. Its greatest king, [[Nebuchadnezzar II]] rivalled another non native ruler, the ethnically unrelated [[Amorite]] king [[Hammurabi]], as the greatest king of Babylon. However, by 556 BC the Chaldeans had been deposed from power by the Assyrian born [[Nabonidus]] and his son and regent [[Belshazzar]]. |

|||

In the 6th century BC, [[Cyrus the Great]] of neighbouring [[Achaemenid Empire|Persia]] defeated the [[Neo-Babylonian Empire]] at the [[Battle of Opis]] and Iraq was subsumed into the [[Achaemenid Empire]] for nearly two centuries. The Achaemenids made [[Babylon]] their main capital. The Chaldeans and Chaldea disappeared at around this time, though both Assyria and Babylonia endured and thrived under Achaemenid rule (see [[Achaemenid Assyria]]). Little changed under the Persians, having spent three centuries under Assyrian rule, their kings saw themselves as successors to Ashurbanipal, and they retained Assyrian Imperial Aramaic as the language of empire, together with the Assyrian imperial infrastructure, and an Assyrian style of art and architecture. |

|||

[[File:Diadochen1.png|thumb|The Greek-ruled [[Seleucid Empire]] (in yellow) with capital in [[Seleucia]] on the Tigris, north of Babylon.]] |

|||

In the late 4th century BC, [[Alexander the Great]] conquered the region, putting it under [[Hellenistic civilization|Hellenistic]] [[Seleucid Empire|Seleucid]] rule for over two centuries.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.umich.edu/~kelseydb/Excavation/Seleucia.html |title=Seleucia on the Tigris |publisher=Umich.edu |date=1927-12-29 |accessdate=2011-06-19}}</ref> The Seleucids introduced the [[Indo-Anatolian]] and [[Greek language|Greek]] term ''Syria'' to the region. This name had for many centuries been the Indo-European word for ''Assyria'' and specifically and only meant Assyria, however the Seleucids also applied it to [[The Levant]] ([[Aramea]], causing both the Assyria and the Assyrians of Iraq and the [[Arameans]] and The Levant to be called Syria and Syrians/Syriacs in the [[Greco-Roman]] world.<ref>Rollinger, Robert (2006). "The terms "Assyria" and "Syria" again" (PDF). Journal of Near Eastern Studies 65 (4): 284–287. doi:10.1086/511103.</ref> |

|||

The [[Parthian Empire|Parthians]] (247 BC – 224 AD) from Persia conquered the region during the reign of [[Mithridates I of Parthia]] (r. 171–138 BC). From [[Syria (Roman province)|Syria]], the [[Roman Empire|Romans]] invaded western parts of the region [[Roman-Parthian Wars|several times]], briefly founding ''Assyria Provincia'' in Assyria. [[Christianity]] began to take hold in Iraq (particularly in [[Assyria]]) between the 1st and 3rd centuries, and Assyria became a centre of [[Syriac Christianity]], the [[Church of the East]] and [[Syriac literature]]. A number of indigenous independent [[Neo-Assyrian]] states evolved in the north during the Parthian era, such as [[Adiabene]], [[Assur]], [[Osroene]] and [[Hatra]]. |

|||

A number of Assyrians from Mesopotamia were conscripted into or joined the [[Roman Army]], and the Aramaic language of Assyria and Mesopotamia has been found as far afield as [[Hadrians Wall]] in northern [[Ancient Britain]], with inscriptions written by [[Assyria (Roman province)|Assyria]]n and [[Aramean]] soldiers of the Roman Empire.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.theguardian.com/culture/charlottehigginsblog/2009/oct/13/hadrians-wall|title=When Syrians, Algerians and Iraqis patrolled Hadrian's Wall|author=Charlotte Higgins|work=the Guardian}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Sassanid dynasty|Sassanids]] of Persia under [[Ardashir I]] destroyed the Parthian Empire and conquered the region in 224 AD. During the 240s and 250's AD the Sassanids gradually conquered the small Neo Assyrian states, culminating with Assur in 256 AD. The region was thus a province of the [[Sassanid Empire]] for over four centuries (see also; [[Asōristān]]), and became the frontier and battle ground between the Sassanid Empire and [[Byzantine Empire]], with both empires weakening each other greatly, paving the way for the [[Arab]]-[[Muslim conquest of Persia]] in the mid-7th century, |

|||

===Middle Ages=== |

|||

[[File:Abbasids Baghdad Iraq 1244.JPG|thumb|left|Abbasid-era coin, Baghdad, 1244.]] |

|||

[[File:Abbasid Caliphate and Umayyad Emirate.png|thumb|280px|The capital city of the [[Abbasid Caliphate]] was Baghdad, c. 755.]] |

|||

The Arab Islamic conquest in the mid-7th century AD established [[Islam]] in Iraq and saw a large influx of [[Arabs]]. Under the [[Rashidun Caliphate]], the prophet [[Muhammad]]'s cousin and son-in-law, [[Ali]], moved his capital to [[Kufa]] when he became the fourth [[caliph]]. The [[Umayyad Caliphate]] ruled the province of Iraq from [[Damascus]] in the 7th century. (However, eventually there was a separate, independent [[Caliphate of Córdoba]] in Iberia.) |

|||

The [[Abbasid Caliphate]] built the city of [[Baghdad]] in the 8th century as its capital, and the city became the leading metropolis of the [[Arab world|Arab]] and [[Muslim world]] for five centuries. Baghdad was the largest [[multiculturalism|multicultural]] [[city]] of the [[Middle Ages]], peaking at a population of more than a million,<ref>{{cite web|url= http://geography.about.com/library/weekly/aa011201a.htm |title=Largest Cities Through History |publisher= Geography.about.com |date=2011-04-06 |accessdate= 2011-06-19}}</ref> and was the centre of learning during the [[Islamic Golden Age]]. The [[Mongol Empire|Mongols]] destroyed the city during the [[Siege of Baghdad (1258)|siege of Baghdad]] in the 13th century.<ref>{{cite web|url= https://web.archive.org/web/20090815080358/http://www.acs.ucalgary.ca/applied_history/tutor/islam/learning/conclusion.html |title= The Islamic World to 1600: The Arts, Learning, and Knowledge (Conclusion) |publisher= Acs.ucalgary.ca }}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Hulagu Baghdad 1258.jpg|thumb|The [[Siege of Baghdad (1258)|sack of Baghdad]] by the Mongols.]] |

|||

In 1257 [[Hulagu Khan]] amassed an unusually large army, a significant portion of the Mongol Empire's forces, for the purpose of conquering Baghdad. When they arrived at the Islamic capital, Hulagu Khan demanded surrender but the last Abbasid Caliph [[Al-Musta'sim]] refused. This angered Hulagu, and, consistent with Mongol strategy of discouraging resistance, he [[Siege of Baghdad (1258)|besieged Baghdad]], sacked the city and massacred many of the inhabitants.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.sfusd.k12.ca.us/schwww/sch618/Ibn_Battuta/Battuta's_Trip_Three.html |title= Battuta's Travels: Part Three – Persia and Iraq |publisher=Sfusd.k12.ca.us |accessdate= 2010-04-21| archiveurl = //web.archive.org/web/20080423014420/http://www.sfusd.k12.ca.us/schwww/sch618/Ibn_Battuta/Battuta's_Trip_Three.html| archivedate = April 23, 2008}}</ref> Estimates of the number of dead range from 200,000 to a million.<ref>{{cite web|last= Frazier |first= Ian |url= http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2005/04/25/050425fa_fact4?currentPage=4 |title= Annals of history: Invaders: Destroying Baghdad |publisher= The New Yorker |date= 2005-04-25 |page= 4 |accessdate=2013-01-25}}</ref> |

|||

The Mongols destroyed the Abbasid Caliphate and Baghdad's [[House of Wisdom]], which contained countless precious and historical documents. The city has never regained its previous pre-eminence as a major centre of culture and influence. Some historians believe that the Mongol invasion destroyed much of the [[irrigation]] infrastructure that had sustained Mesopotamia for millennia. Other historians point to [[soil salination]] as the culprit in the decline in agriculture.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.waterencyclopedia.com/Hy-La/Irrigation-Systems-Ancient.html |title= Irrigation Systems, Ancient |publisher= Waterencyclopedia.com |date=2009-01-11 |accessdate=2010-04-21}}</ref> |

|||

The mid-14th-century [[Black Death]] ravaged much of the [[Islamic world]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ucalgary.ca/applied_history/tutor/islam/mongols/blackDeath.html |title=The Islamic World to 1600: The Mongol Invasions (The Black Death) |publisher=The University of Calgary |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/20090131180742/http://www.ucalgary.ca:80/applied_history/tutor/islam/mongols/blackDeath.html |archivedate=January 31, 2009 }}</ref> The best estimate for the Middle East is a death rate of roughly one-third.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://liveweb.archive.org/http://old.nationalreview.com/interrogatory/kelly200509140843.asp|title=Q&A with John Kelly on The Great Mortality on National Review Online |publisher=Nationalreview.com |date=2005-09-14 |accessdate=2009-03-23}}</ref> |

|||

In 1401 a warlord of Mongol descent, [[Tamerlane]] (Timur Lenk), invaded Iraq. After the capture of Baghdad, 20,000 of its citizens were massacred.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://asianhistory.about.com/od/profilesofasianleaders/p/TimurProf.htm |title= Tamerlane – Timur the Lame Biography |publisher= Asianhistory.about.com |date= 2010-02-15 |accessdate=2010-04-21}}</ref> Timur ordered that every soldier should return with at least two severed human heads to show him (many warriors were so scared they killed prisoners captured earlier in the campaign just to ensure they had heads to present to Timur).<ref>{{cite web |url=http://mertsahinoglu.com/research/14th-century-annihilation-of-iraq |title= 14th century annihilation of Iraq |publisher= Mert Sahinoglu |accessdate= 2011-06-19}}</ref> Timur also conducted massacres of the indigenous [[Assyrian people|Assyrian]] [[Christian]] population, hitherto still the majority population in northern Mesopotamia, and it was during this time that the ancient Assyrian city of [[Assur]] was finally abandoned.<ref> |

|||

^ Nestorians, or Ancient Church of the East at Encyclopædia Britannica |

|||

</ref> |

|||

===Ottoman Iraq=== |

|||

{{main|Ottoman Iraq|Mamluk dynasty of Iraq}} |

|||

[[File:Cedid Atlas (Middle East) 1803.jpg|thumb|left|1803 [[Cedid Atlas]], showing the area today known as Iraq divided between "[[Upper Mesopotamia|Al Jazira]]" (pink), "[[Kurdistan]]" (blue), "Iraq" (green), and "[[Al Sham]]" (yellow).]] |

|||

During the late 14th and early 15th centuries, the [[Black Sheep Turkmen]] ruled the area now known as Iraq. In 1466, the [[White Sheep Turkmen]] defeated the Black Sheep and took control. From the earliest 16th cenntury, in 1508, as with all territories of the former White Sheep Turkmen, Iraq fell into the hands of the Iranian [[Safavids]]. Owing to the century long Turco-Iranian rivalary between the Safavids and the neighbouring [[Ottoman Turks]], Iraq would be contested between the two for more than a hundred years during the frequent [[Ottoman-Persian Wars]]. In the course of the 17th century, in 1639 precisely with the [[Treaty of Zuhab]], most of the territory of present-day Iraq eventually decisively came under the control of Ottoman Empire as the [[eyalet of Baghdad]] as a result of [[Ottoman-Persian Wars|wars]] with neighbouring rivalling [[Safavid dynasty|Safavid Iran]]. Throughout most of the period of Ottoman rule (1533–1918) the territory of present-day Iraq was a battle zone between the rival regional empires and tribal alliances. |

|||

By the 17th century, the frequent conflicts with the Safavids had sapped the strength of the Ottoman Empire and had weakened its control over its provinces. The nomadic population swelled with the influx of [[bedouin]]s from [[Najd]], in the Arabian Peninsula. Bedouin raids on settled areas became impossible to curb.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://countrystudies.us/iraq/18.htm |title=Iraq – The Ottoman Period, 1534–1918 |publisher=Countrystudies.us |accessdate=2011-06-19}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Layard Nineveh.jpg|thumb|240px|English archaeologist [[Austen Henry Layard]] in the ancient [[Assyria]]n city of [[Nineveh]], 1852.]] |

|||

During the years 1747–1831 Iraq was ruled by a [[Mamluk dynasty of Iraq|Mamluk dynasty]] of [[Georgian people|Georgian]]<ref name="bbs">{{cite book|author=Reidar Visser|title=Basra, the Failed Gulf State: Separatism And Nationalism in Southern Iraq|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pCC4ffbOv_YC&pg=PA19|year=2005|publisher=LIT Verlag Münster|isbn=978-3-8258-8799-5|page=19}}</ref> origin who succeeded in obtaining autonomy from the [[Ottoman Porte]], suppressed tribal revolts, curbed the power of the Janissaries, restored order and introduced a programme of modernisation of economy and military. In 1831, the Ottomans managed to overthrow the Mamluk regime and imposed their direct control over Iraq. The population of Iraq, estimated at 30 million in 800 AD, was only 5 million at the start of the 20th century.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.valerieyule.com.au/poprus.htm |title=Population crises and cycles in history A review of the book ''Population Crises and Population cycles'' by Claire Russell and W.M.S. Russell. ISBN 0-9504066-5-1 |publisher=valerieyule.com.au}}</ref> |

|||

During [[World War I]], the Ottomans sided with [[Germany]] and the [[Central Powers]]. In the [[Mesopotamian campaign]] against the Central Powers, [[United Kingdom|British]] forces invaded the country and initially suffered a major defeat at the hands of the Turkish army during the [[Siege of Kut]] (1915–1916). However, subsequent to this the British began to gain the upper hand, and were further aided by the support of local [[Arabs]] and [[Assyrians in Iraq|Assyrians]]. In 1916, the British and French made a plan for the post-war division of [[Western Asia]] under the [[Sykes-Picot Agreement]].<ref>[http://www.law.fsu.edu/library/collection/limitsinSeas/IBSo94.pdf p.8]{{Dead link|date=April 2010}}</ref> British forces regrouped and [[Fall of Baghdad (1917)|captured Baghdad]] in 1917, and defeated the Ottomans. An armistice was signed in 1918. |

|||

During World War I the Ottomans were defeated and driven from much of the area by the United Kingdom during the [[dissolution of the Ottoman Empire]]. The British lost 92,000 soldiers in the Mesopotamian campaign. Ottoman losses are unknown but the British captured a total of 45,000 [[prisoner of war|prisoners of war]]. By the end of 1918 the British had deployed 410,000 men in the area, of which 112,000 were combat troops.{{citation needed|date=June 2014}} |

|||

===British administration and independent Kingdom=== |

|||

{{main|Kingdom of Iraq (Mandate administration)|Kingdom of Iraq (1932–58)}} |

|||

[[File:BritsLookingOnBaghdad1941.jpg|thumb|British troops in Baghdad, June 1941.]] |

|||

On 11 November 1920 Iraq became a [[League of Nations mandate]] under British control with the name "[[British Mandate of Mesopotamia|State of Iraq]]". The British established the [[Hashemite]] king, [[Faisal I of Iraq]], who had been forced out of [[Syria]] by the French, as their client ruler. Likewise, British authorities selected Sunni Arab elites from the region for appointments to government and ministry offices.<!-- in Iraq or Iraq and its neighbouring regions? -->{{Specify|date=April 2007}}<ref>{{cite book|last=Tripp|first=Charles|title=A History of Iraq|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WR-Cnw1UCJEC|year=2002|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-52900-6}}</ref>{{page needed|date=February 2013}} |

|||

Faced with spiraling costs and influenced by the public protestations of war hero [[T. E. Lawrence]]<ref> |

|||

{{cite book|first1=Jeremy |last1=Wilson |authorlink=Jeremy Wilson |title=Lawrence of Arabia: The Authorised Biography of T. E. Lawrence|date=1998|publisher=Sutton|location=Stroud|isbn=0750918772|url=https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=OsEhAQAAIAAJ&q=%22Lawrence+of+Arabia%22&dq=%22Lawrence+of+Arabia%22&hl=en&sa=X&ei=ruwjVeanJsfZaofAgeAG&ved=0CCAQ6AEwAA|quote=The exploits of T.E. Lawrence as British liaison officer in the Arab Revolt, recounted in his work Seven Pillars of Wisdom, made him one of the most famous Englishmen of his generation. This biography explores his life and career including his correspondence with writers, artists and politicians.}}</ref> |

|||

in ''[[The Times]]'', Britain replaced [[Arnold Wilson]] in October 1920 with new Civil Commissioner [[Percy Zachariah Cox|Sir Percy Cox]].{{citation needed|date=June 2014}} Cox managed to quell a rebellion, yet was also responsible for implementing the fateful policy of close co-operation with Iraq's Sunni minority.<ref>{{cite book|author1=Liam Anderson|author2=Gareth Stansfield|title=The Future of Iraq: Dictatorship, Democracy, Or Division?|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4JMHAI1C91gC&pg=PA6|year=2005|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan|isbn=978-1-4039-7144-9|page=6|quote=Sunni control over the levels of power and the distribution of the spoils of office has had predictable consequences- a simmering resentment on the part of the Shi'a...}}</ref> The institution of [[slavery]] was abolished in the 1920s.<ref name="zanj"/> |

|||

Britain granted independence to the [[Kingdom of Iraq]] in 1932,<ref>Ongsotto et.al. ''Asian History Module-based Learning Ii' 2003 Ed''. p69. [https://books.google.co.il/books?id=KE6f6Ni5lrsC&pg=PR7&lpg=PR7&dq=asian+history+module+based+learning&source=bl&ots=S7dsbT75jf&sig=IqWlp3Yj6vxv3SI0aTUTyBeqwZE&hl=iw&sa=X&ei=r3jjVLjZIsKrU9Kgg-gK&ved=0CCEQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=asian%20history%20module%20based%20learning&f=false]</ref> on the urging of [[Faisal I of Iraq|King Faisal]], though the British retained [[military base]]s, local militia in the form of [[Assyrian Levies]], and transit rights for their forces. King [[Ghazi of Iraq|Ghazi]] ruled as a figurehead after King Faisal's death in 1933, while undermined by attempted military [[coup d'état|coups]], until his death in 1939. Ghazi was followed by his underage son, [[Faisal II of Iraq|Faisal II]]. [['Abd al-Ilah]] served as [[Regent]] during Faisal's minority. |

|||

On 1 April 1941, [[Rashid Ali al-Gaylani]] and members of the [[Golden Square (Iraq)|Golden Square]] staged a [[1941 Iraqi coup d'état|coup d'état and overthrew the government of 'Abd al-Ilah]]. During the subsequent [[Anglo-Iraqi War]], the [[United Kingdom]] (which still maintained air bases in Iraq) invaded Iraq for fear that the Rashid Ali government might cut oil supplies to Western nations because of his links to the [[Axis powers]]. The war started on 2 May, and the British, together with loyal [[Assyrian Levies]],<ref>Lyman, p.23</ref> defeated the forces of Al-Gaylani, forcing an armistice on 31 May. |

|||

A [[military occupation]] followed the restoration of the pre-coup government of the [[Hashemite]] monarchy. The occupation ended on 26 October 1947, although Britain was to retain military bases in Iraq until 1954, after which the Assyrian militias were disbanded. The rulers during the occupation and the remainder of the Hashemite monarchy were [[Nuri as-Said]], the autocratic Prime Minister, who also ruled from 1930–1932, and 'Abd al-Ilah, the former Regent who now served as an adviser to King Faisal II. |

|||

===Republic and Ba'athist Iraq=== |

|||

{{main|Iraqi Republic (1958–68)|Ba'athist Iraq|Iran–Iraq War}} |

|||

[[File:1958 revolution in Iraq.jpg|thumb|The [[14 July Revolution]] in 1958.]] |

|||

In 1958 a [[coup d'etat]] known as the [[14 July Revolution]] led to the end of the monarchy. Brigadier General [[Abd al-Karim Qasim]] assumed power, but he was overthrown by Colonel [[Abdul Salam Arif]] in a [[February 1963 Iraqi coup d'état|February 1963 coup]]. After his death in 1966 he was succeeded by his brother, [[Abdul Rahman Arif]], who was overthrown by the [[Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party – Iraq Region|Ba'ath Party]] in 1968. [[Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr]] became the first Ba'ath [[President of Iraq]] but then the movement gradually came under the control of General [[Saddam Hussein]], who acceded to the presidency and control of the [[Iraqi Revolutionary Command Council|Revolutionary Command Council]] (RCC), then Iraq's supreme executive body, in July 1979. |

|||

After the success of the 1979 [[Iranian Revolution]], President Saddam Hussein initially welcomed the overthrow of the Shah and sought to establish good relations with [[Ayatollah Khomeini]]'s new government. However, Khomeini openly called for the spread of the Islamic Revolution to Iraq, arming Shiite and Kurdish rebels against Saddam's regime and sponsoring assassination attempts on senior Iraqi officials. Following months of cross-border raids between the two countries, Saddam declared war on Iran in September 1980, initiating the [[Iran–Iraq War]] (or First Persian Gulf War). Iraq withdrew from Iran in 1982, and for the next six years Iran was on the offensive.<ref>{{cite book|last=Karsh|first=Efraim|title=The Iran–Iraq War, 1980–1988|year=2002|publisher=Osprey Publishing|location=Oxford, Oxfordshire|isbn=978-1841763712}}</ref>{{page needed|date=July 2014}} The war ended in [[stalemate]] in 1988 and cost the lives of between half a million and 1.5 million people.<ref>{{cite news|last=Hardy |first=Roger |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/4260420.stm |title=The Iran–Iraq war: 25 years on |publisher=BBC News |date=2005-09-22 |accessdate=2011-06-19}}</ref> In 1981, Israeli aircraft [[Operation Opera|bombed an Iraqi nuclear materials testing reactor at Osirak]] and was widely criticised at the United Nations.<ref>S-RES-487(1981) Security Council Resolution 487 (1981)". United Nations. Retrieved 19 June 2011., http://domino.un.org/UNISPAL.NSF/0/6c57312cc8bd93ca852560df00653995?OpenDocument</ref><ref>Jonathan Steele (7 June 2002). "The Bush doctrine makes nonsense of the UN charter". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2010, http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2002/jun/07/britainand911.usa</ref> Iraq waged [[Iraqi chemical weapons program|chemical warfare]] against Iran.<ref>Tyler, Patrick E. [http://www.nytimes.com/2002/08/18/world/officers-say-us-aided-iraq-in-war-despite-use-of-gas.html "Officers Say U.S. Aided Iraq in War Despite Use of Gas"] ''New York Times'' August 18, 2002.</ref> In the final stages of Iran–Iraq War, the Ba'athist Iraqi regime led the [[Al-Anfal Campaign]], a [[genocidal]]<ref name="hrw.org">{{cite web|url=http://www.hrw.org/en/reports/2006/08/14/genocide-iraq-anfal-campaign-against-kurds |title=The Anfal Campaign Against the Kurds A Middle East Watch Report |publisher=Human Rights Watch |date=2006-08-14 |accessdate=2013-01-25}}</ref> campaign that targeted Iraqi Kurds,<ref>{{cite book |last=Black |first=George|title=Genocide in Iraq: The Anfal Campaign against the Kurds / Western Asia Watch |origyear=1993 |url=http://hrw.org/reports/1993/iraqanfal/|accessdate=2007-02-10 |publisher=Human Rights Watch |location=New York • Washington • Los Angeles • London|isbn=1-56432-108-8 |date=July 1993}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last=Hiltermann |first=Joost R.|title=Bureaucracy of Repression: The Iraqi Government in Its Own Words / Western Asia Watch |origyear=1994 |url=http://www.hrw.org/reports/1994/iraq/TEXT.htm |archiveurl=//web.archive.org/web/20061028211739/http://www.hrw.org/reports/1994/iraq/TEXT.htm |archivedate=2006-10-28 |accessdate=2007-02-10 |publisher=Human Rights Watch |isbn=1-56432-127-4|date=February 1994}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.institutkurde.org/en/afp/archives/070108093217.hrifbdh6.html |archiveurl=//web.archive.org/web/20090101055802/http://www.institutkurde.org/en/afp/archives/070108093217.hrifbdh6.html |archivedate=2009-01-01 |title=Charges against Saddam dropped as genocide trial resumes |publisher=Agence France-Presse |date=January 8, 2007}}</ref> and led to the killing of 50,000–100,000 civilians.<ref>{{cite book|last=Hiltermann|first=J. R.|title=A Poisonous Affair: America, Iraq, and the Gassing of Halabja|year=2007|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-87686-5|pages=134–135|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5JGldonhk6wC&pg=PA134}}</ref> |

|||

In August 1990, [[Invasion of Kuwait|Iraq invaded and annexed Kuwait]]. This subsequently led to [[Gulf War|military intervention]] by [[United States]]-led forces in the First [[Gulf War]]. The coalition forces proceeded with a bombing campaign targeting military targets<ref name=Crusade>{{cite book|author=Rick Atkinson|title=Crusade: The Untold Story of the Persian Gulf War|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TVVwADcYOcgC&pg=PA284|year=1993|publisher=Houghton Mifflin Harcourt|isbn=978-0-395-71083-8|pages=284–285}}</ref><ref name=Arbuthnot>{{cite web|url=http://www.uruknet.de/?p=m30603&hd=&size=1&l=e |title=The Ameriya Shelter – St. Valentine's Day Massacre |publisher=Uruknet.de |accessdate=2011-06-19}}</ref><ref name=CSM2002>{{cite web|url=http://www.csmonitor.com/2002/1022/p01s01-wosc.htm |title='Smarter' bombs still hit civilians |work=Christian Science Monitor |date=2002-10-22 |accessdate=2011-06-19}}</ref> and then launched a 100-hour-long ground assault against Iraqi forces in Southern Iraq and those occupying Kuwait. |

|||

Iraq's armed forces were devastated during the war and shortly after it ended in 1991, [[Shia]] and Kurdish Iraqis led [[1991 uprisings in Iraq|several uprisings]] against [[Saddam Hussein]]'s regime, but these were successfully repressed using the Iraqi security forces and chemical weapons. It is estimated that as many as 100,000 people, including many civilians were killed.<ref>{{cite news|author=Ian Black |url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2007/aug/22/iraq.ianblack |title='Chemical Ali' on trial for brutal crushing of Shia uprising |work=The Guardian |date=2007-08-22|accessdate=2011-06-19 |location=London}}</ref> During the uprisings the US, UK, France and Turkey, claiming authority under [[United Nations Security Council Resolution 688|UNSCR 688]], established the [[Iraqi no-fly zones]] to protect Kurdish and Shiite populations from attacks by the Hussein regime's fixed-wing aircraft (but not helicopters). |

|||

[[File:Saddam Hussain Iran-Iraqi war 1980s.jpg|thumb|Saddam Hussein during the [[Iran–Iraq War]]. Hussein ruled Iraq from 1979 until 2003.]] |

|||

Iraq was ordered to destroy its chemical and biological weapons and the UN attempted to compel Saddam Hussein's government to disarm and agree to a ceasefire by imposing additional sanctions on the country in addition to the initial sanctions imposed following Iraq's invasion of Kuwait. The Iraqi Government's failure to disarm and agree to a ceasefire resulted in [[Iraq sanctions|sanctions]] which remained in place until 2003. Studies dispute the effects of the sanctions on Iraqi civilians.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.unicef.org/newsline/99pr29.htm|title=Iraq surveys show 'humanitarian emergency' |date=12 August 1999|accessdate=29 November 2009}}</ref><ref name=Spagat>{{cite journal|last=Spagat|first=Michael|title=Truth and death in Iraq under sanctions|journal=Significance|date=8 July 2010|volume=7|issue=3|pages=116–120|doi=10.1111/j.1740-9713.2010.00437.x|url=http://personal.rhul.ac.uk/uhte/014/Truth%20and%20Death.pdf}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Rubin |first=Michael |title=Sanctions on Iraq: A Valid Anti-American Grievance? |work=[[Middle East Review of International Affairs]] |volume=5 |issue=4 |url=http://www.iraqwatch.org/perspectives/meria-rubin-sanctions-1201.htm |pages=100–115 |date=December 2001 |authorlink=Michael Rubin}}</ref> |

|||

During the late 1990s, the UN considered relaxing the [[Iraq sanctions]] because of the hardships suffered by ordinary Iraqis{{citation needed|date=June 2014}} and attacks on US aircraft patrolling the no-fly zones led to [[Bombing of Iraq (December 1998)|US bombing of Iraq in December 1998]]. |

|||

Following the [[9/11 terrorist attacks]] the [[Presidency of George W. Bush|George W. Bush administration]] began planning the overthrow of Saddam Hussein's government and in October 2002, the US Congress passed the [[Joint Resolution to Authorize the Use of United States Armed Forces Against Iraq]]. In November 2002 the UN Security Council passed [[United Nations Security Council Resolution 1441|UNSCR 1441]] and in March 2003 the US and its allies invaded Iraq. |

|||

===2003–2007=== |

|||

[[File:SaddamStatue.jpg|thumb|upright|right|float|The April 2003 toppling of [[Saddam Hussein]]'s statue in [[Firdos Square]] in [[Baghdad]] shortly after the [[Iraq War]] invasion.]] |

|||

{{Main|2003 invasion of Iraq|History of Iraq (2003–11)|Iraq War}} |

|||

On March 20, 2003, a United States-organized coalition [[2003 invasion of Iraq|invaded Iraq]], under the pretext that Iraq had failed to abandon its [[Iraq and weapons of mass destruction|weapons of mass destruction program]] in violation of [[United Nations Security Council Resolution 687|U.N. Resolution 687]]. This claim was based on documents provided by the [[CIA]] and British government<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.factcheck.org/bushs_16_words_on_iraq_uranium.html |archiveurl=//web.archive.org/web/20100305071446/http://www.factcheck.org/bushs_16_words_on_iraq_uranium.html |archivedate=2010-03-05 |title=Bush's "16 Words" on Iraq & Uranium: He May Have Been Wrong But He Wasn't Lying |publisher=FactCheck.org |date=July 26, 2004}}{{dead link|date=March 2015}}</ref> and were later [[Duelfer Report|found to be unreliable]].<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2004/oct/07/usa.iraq1 |title=There were no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq |accessdate=2008-04-28 |last=Borger |first=Julian |date=2004-10-07 |publisher=[[Guardian Media Group]] |work=[[guardian.co.uk]] |location=London}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=John Simpson: 'The Iraq memories I can't rid myself of'|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-21829269|publisher=BBC News|accessdate=19 March 2013|date=2013-03-19}}</ref> |

|||

Following the invasion, the United States established the [[Coalition Provisional Authority]] to govern Iraq. In May 2003 [[L. Paul Bremer]], the chief executive of the CPA, issued orders to [[De-Ba'athification|exclude Baath Party members]] from the new Iraqi government (CPA Order 1) and to disband the Iraqi Army ([[Coalition Provisional Authority Order 2|CPA Order 2]]).<ref>{{cite journal|last=Pfiffner|first=James|title=US Blunders in Iraq: De-Baathification and Disbanding the Army|journal=Intelligence and National Security|date=February 2010|volume=25|issue=1|pages=76–85|doi=10.1080/02684521003588120|url=http://pfiffner.gmu.edu/files/pdfs/Articles/CPA%20Orders,%20Iraq%20PDF.pdf|accessdate=16 December 2013}}</ref> The decision dissolved the largely Sunni Iraqi Army<ref>{{cite news|title=Fateful Choice on Iraq Army Bypassed Debate|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/17/world/middleeast/17bremer.html?pagewanted=all|publisher=New York Times|date=2008-03-17|first=Michael R.|last=Gordon}}</ref> and excluded many of the country's former government officials from participating in the country's governance including 40,000 school teachers who had joined the Baath Party simply to keep their jobs,<ref>[http://pfiffner.gmu.edu/files/pdfs/Articles/CPA%20Orders,%20Iraq%20PDF.pdf " US Blunders in Iraq" ] "Intelligence and National Security Vol. 25, No. 1, 76–85, February 2010"</ref> helping to bring about a chaotic post-invasion environment.<ref>{{cite news|title=Can the joy last?|url=http://www.economist.com/node/21528299|work=The Economist|date=2011-09-03}}</ref> |

|||

[[Iraqi insurgency (2003–06)|An insurgency]] against the [[2003 invasion of Iraq|US-led coalition]]-rule of Iraq began in summer 2003 within elements of the former Iraqi secret police and army who formed guerilla units. In fall 2003, also self-entitled ‘[[jihad]]ist’ groups began targeting coalition forces. |

|||

Various Sunni militias were created in 2003, for example [[Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad]] led by [[Abu Musab al-Zarqawi]]. |

|||

The insurgency included intense inter-ethnic violence between Sunnis and Shias.<ref name="cnn.com">{{cite news |title=U.S. cracks down on Iraq death squads |url=http://www.cnn.com/2006/WORLD/meast/07/24/iraq.main/index.html |publisher=CNN |date=24 July 2006}}</ref> The [[Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse]] scandal came to light, late 2003 in reports by [[Amnesty International]] and [[Associated Press]]. |

|||

[[File:US Navy 031016-N-3236B-043 A marine patrols the streets of Al Faw, Iraq.jpg|thumb|left|[[United States Marine Corps|US Marines]] patrol the streets of [[Al Faw]], October 2003.]] |

|||

The [[Mahdi Army]]—a Shia militia created in the summer of 2003 by [[Muqtada al-Sadr]]<ref name=mehdi />—began to fight Coalition forces in April 2004.<ref name=mehdi>{{cite news|title=Who are Iraq's Mehdi Army?|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/3604393.stm|publisher=BBC News|accessdate=2013-03-04|date=2007-05-30|first=Patrick|last=Jackson}}</ref> 2004 saw Sunni and Shia militants fighting against each other and against the new [[Iraqi Interim Government]] installed June 2004, and against Coalition forces, as well as the [[First Battle of Fallujah]] in April and [[Second Battle of Fallujah]] in November. |

|||

Sunni militia Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad became [[Al-Qaeda in Iraq]] in October 2004 and targeted Coalition forces as well as civilians, mainly Shia Muslims, further exacerbating ethnic tensions.<ref>{{cite news|title=Al Qaeda's hand in tipping Iraq toward civil war|url=http://www.csmonitor.com/2006/0320/p09s01-coop.html|newspaper=Christian Science Monitor / Al-Quds Al-Arabi|date=2006-03-20}}</ref> |

|||

In January 2005 the [[Iraqi parliamentary election, January 2005|first elections]] since the invasion took place and in October a [[Constitution of Iraq|new Constitution]] was approved which was followed by [[Iraqi parliamentary election, December 2005|parliamentary elections]] in December. Insurgent attacks were common however and increased to 34,131 in 2005 from 26,496 in 2004.<ref>Thomas Ricks (2006) ''Fiasco'': 414</ref> |

|||

During 2006 fighting continued and reached its highest levels of violence, more [[Haditha killings|war crimes scandals]] were made public, [[Abu Musab al-Zarqawi]] the leader of [[Al-Qaeda in Iraq]] was killed by US forces and Iraq's former dictator [[Saddam Hussein]] was sentenced to death for [[crimes against humanity]] and hanged.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/6219861.stm|title=Saddam death 'ends dark chapter'|publisher=BBC News|date=2006-12-30|accessdate = 2007-08-18}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601087&sid=adlWxYxfI4bE|title=Saddam Hussein's Two Co-Defendants Hanged in Iraq|publisher=[[Bloomberg L.P.]]|date=2007-01-15|accessdate = 2007-08-18}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory?id=2965027|archiveurl=//web.archive.org/web/20070323194534/http://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory?id=2965027|archivedate=2007-03-23|title=Saddam's Former Deputy Hanged in Iraq|author=Qassim Abdul-Zahra |date=2007-03-20 |publisher=Abcnews.go.com |accessdate=2009-03-23}}</ref> |

|||

In late 2006 the US government's [[Iraq Study Group]] recommended that the US begin focusing on training Iraqi military personnel and in January 2007 US President George W. Bush announced a [[Iraq War troop surge of 2007|"Surge"]] in the number of US troops deployed to the country.<ref>{{cite web |last=Ferguson |first=Barbara |title=Petraeus Says Iraq Troop Surge Working |work=Arab News |date=11 September 2007 |url=http://www.arabnews.com/?page=4§ion=0&article=101078&d=11&m=9&y=2007 |accessdate=26 December 2009}}</ref> |

|||

In May 2007 Iraq's Parliament called on the United States to set a timetable for withdrawal<ref>[http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,271210,00.html Iraq Bill Demands U.S. Troop Withdraw] Associated Press, ''[[Fox News]]'', 10 May 2007</ref> and US coalition partners such as the UK and Denmark began withdrawing their forces from the country.<ref>BBC NEWS 21 February 2007, [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/politics/6380933.stm ''Blair announces Iraq troops cut'']</ref><ref>[[Al-Jazeera]] ENGLISH, 21 February 2007, [http://english.aljazeera.net/NR/exeres/70F3CDDC-B326-45FC-9A2F-85F9E74FBF8C.htm Blair announces Iraq troop pullout]{{Dead link|date=April 2014}}</ref> The war in Iraq has resulted in [[Casualties of the Iraq War|between 151,000 and 1.2 million Iraqis being killed]].<ref>"[http://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/jan/10/iraq.iraqtimeline 151,000 civilians killed since Iraq invasion]". ''[[The Guardian]]''. 10 January 2008.</ref><ref>"[http://articles.latimes.com/2007/sep/14/world/fg-iraq14 Civilian deaths may top 1 million, poll data indicate]". ''[[Los Angeles Times]]''. 14 September 2007.</ref> |

|||

===2008–present=== |

|||

{{main|2008 in Iraq|2009 in Iraq|2010 in Iraq|2011 in Iraq|2012 in Iraq|2013 in Iraq|2014 in Iraq}} |

|||

In 2008 [[Iraq spring fighting of 2008|fighting continued]] and Iraq's newly trained armed forces launched attacks against militants. The Iraqi government signed the [[US–Iraq Status of Forces Agreement]] which required US forces to withdraw from Iraqi cities by 30 June 2009 and to withdraw completely out of Iraq by 31 December 2011. |

|||

US troops handed over security duties to Iraqi forces in June 2009, though they continued to work with Iraqi forces after the pullout.<ref>{{cite news |title=US soldiers leave Iraq's cities|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/8125547.stm|work=BBC|date= 2009-06-30|accessdate = 2009-06-30}}</ref> On the morning of 18 December 2011, the final contingent of US troops to be withdrawn ceremonially exited over the border to [[Kuwait]].<ref name="cnn-dec11" /> Crime and violence initially spiked in the months following [[U.S.–Iraq Status of Forces Agreement|the US withdrawal from cities in mid-2009]]<ref name="The Associated Press and Yahoo.com">{{cite news|title=After years of war, Iraqis hit by frenzy of crime|url=http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/32955876/ns/world_news-mideast_n_africa/t/after-years-war-iraqis-hit-frenzy-crime/#.UOs2ZbaqTMg|agency=Associated Press}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Violence Grows in Iraq as American troops withdraw|url=http://www.foxnews.com/politics/2009/05/09/violence-grows-iraq-american-troops-withdraw/|publisher=FOX |date=2009-05-09}}</ref> but despite the initial increase in violence, in November 2009, Iraqi [[Ministry of Interior (Iraq)|Interior Ministry]] officials reported that the civilian death toll in Iraq fell to its lowest level since the 2003 invasion.<ref>{{cite news |title=Iraqi civilian deaths drop to lowest level of war |url=http://www.reuters.com/article/2009/11/30/us-iraq-toll-idUSTRE5AT3ZE20091130 |publisher=Reuters |date=2009-11-30}}</ref> |

|||

Following the [[Withdrawal of U.S. troops from Iraq|withdrawal of US troops]] in 2011 the insurgency continued and Iraq suffered from political instability. In February 2011 the [[Arab Spring]] protests [[2011 Iraqi protests|spread to Iraq]];<ref>{{cite news |title=Egyptian revolution sparks protest movement in democratic Iraq |first=Liz |last=Sly |url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2011/02/12/AR2011021202100.html |work=The Washington Post |date=12 February 2011 |accessdate=12 February 2011}}</ref> but the initial protests did not topple the government. |

|||

The [[Iraqi National Movement]], reportedly representing the majority of Iraqi Sunnis, boycotted Parliament for several weeks in late 2011 and early 2012, claiming that the Shiite-dominated government was striving to sideline Sunnis. |

|||

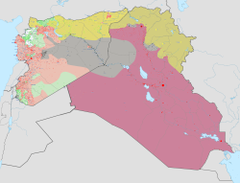

[[File:Syria and Iraq 2014-onward War map.png|thumb|240px|Current military situation, {{#invoke:Iraq_Syria_map_date|date}}:<br />{{legend|#db8ca6|Controlled by [[Federal government of Iraq|Iraqi government]]}}{{legend|#b4b2ae|Controlled by the [[Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant]] (ISIL)}}{{legend|#d7e074|Controlled by [[Peshmerga|Iraqi Kurds]]}}]] |

|||

In 2012 and 2013 levels of violence increased and armed groups inside Iraq were increasingly galvanised by the [[Syrian Civil War]]. Both Sunnis and Shias crossed the border to fight in Syria.<ref name=Kurd-Shiite-Sunni-Split>{{cite web|last=Salem|first=Paul|title=INSIGHT: Iraq’s Tensions Heightened by Syria Conflict|url=http://middleeastvoices.voanews.com/2012/11/insight-iraqs-tensions-heightened-by-syria-conflict-96791/|publisher=Middle East Voices ([[Voice of America]])|accessdate=3 November 2012|date=29 November 2012}}</ref> In December 2012, mainly Sunni Arabs [[2012–13 Iraqi protests|protested]] against the government who they claimed marginalised them.<ref>{{cite news|title=Iraq Sunni protests in Anbar against Nouri al-Maliki|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-20860647|accessdate=22 March 2013|publisher=BBC News|date=28 December 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=Protests engulf west Iraq as Anbar rises against Maliki|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-20887739|accessdate=22 March 2013|publisher=BBC News|date=2 January 2013}}</ref> |

|||

During 2013 Sunni militant groups stepped up attacks targeting the Iraq's [[Shia Islam in Iraq|Shia]] population in an attempt to undermine confidence in the [[Nouri al-Maliki]]-led government.<ref name=latimes2701>{{cite news|title=Suicide bomber kills 32 at Baghdad funeral march|url=http://www.foxnews.com/world/2012/01/27/car-bombing-kills-26-in-baghdad/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed:+foxnews/world+(Internal+-+World+Latest+-+Text)|agency=Associated Press|publisher=Fox News|accessdate=22 April 2012|date=27 January 2012}}</ref> In 2014 Sunni insurgents belonging to the [[Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant]] (ISIL) terrorist group seized control of large swathes of land including several major Iraqi cities, like [[Tikrit]], [[Fallujah]] and [[Mosul]] creating hundreds of thousands of [[internally displaced persons]] amid reports of atrocities by ISIL fighters.<ref>{{cite news|title=Iraq crisis: Battle grips vital Baiji oil refinery|url=http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-27897648|accessdate=18 June 2014|agency=BBC}}</ref> |

|||

After an inconclusive election in April 2014, [[Nouri al-Maliki]] served as caretaker-Prime-Minister.<ref name=guar11-8-14>{{cite web|author=Spencer Ackerman and agencies|url=http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/aug/11/us-iraqi-maliki-accuses-president|title=Kerry slaps down Maliki after he accuses Iraqi president of violating constitution|publisher=The Guardian|date=11 August 2014|accessdate=15 November 2014}}</ref> |

|||

On 11 August, Iraq’s highest court ruled that PM Maliki’s bloc is biggest in parliament, meaning Maliki could stay Prime Minister.<ref name=guar11-8-14/> By 13 August, however, the Iraqi president had tasked [[Haider al-Abadi]] with forming a new government, and the United Nations, the United States, the European Union, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and some Iraqi politicians expressed their wish for a new leadership in Iraq, for example from [[Haider al-Abadi]].<ref>{{cite web|last=Salama|first=Vivian|url=http://www.stripes.com/tensions-high-in-iraq-as-support-for-new-pm-grows-1.297997|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20140813212654/http://www.stripes.com/tensions-high-in-iraq-as-support-for-new-pm-grows-1.297997|archivedate=2014-08-13|title=Tensions high in Iraq as support for new PM grows|publisher=Stripes|date=13 August 2014|accessdate=15 November 2014}}</ref> Maliki on 14 August stepped down as PM, to support Mr al-Abadi and to “safeguard the high interests of the country”. The US government welcomed this as “another major step forward” in uniting Iraq.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/news/world/middleeast/iraq/article4177222.ece|title=White House hails al-Maliki departure as ‘major step forward’|publisher=The Times|date=15 August 2014|accessdate=15 November 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.foxnews.com/world/2014/08/15/iraq-al-maliki-backs-new-prime-minister/|title=Iraq's new prime minister-designate vows to fight corruption, terrorism|publisher=Fox News|date=|accessdate=2014-08-18}}</ref> On September 9, 2014, [[Haider al-Abadi]] had formed a new government and became the new prime minister.{{Citation needed|date=November 2014}} Intermittent conflict between Sunni, [[Shiite]] and Kurdish factions has led to increasing debate about the splitting of Iraq into three autonomous regions, including Kurdistan in the northeast, a [[Sunnistan]] in the west and a Shiastan in the southeast.<ref>The Revenge of Geography, p 353, Robert D. Kaplan - 2012</ref> |

|||

== ఇవీ చూడండి == |

== ఇవీ చూడండి == |

||

08:50, 2 ఫిబ్రవరి 2016 నాటి కూర్పు

| جمهورية العراق జమ్-హూరియత్ అల్-ఇరాక్ كۆماری عێراق Komarê Iraq ఇరాక్ గణతంత్రం |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| నినాదం الله أكبر (అరబ్బీ) "అల్లాహు అక్బర్" (transliteration) "అల్లాహ్ గొప్పవాడు" |

||||||

| జాతీయగీతం Mawtini (new) Ardh Alforatain (previous)1 |

||||||

|

||||||

| రాజధాని | బాగ్దాదు2 33°20′N 44°26′E / 33.333°N 44.433°E | |||||

| అతి పెద్ద నగరం | రాజధాని | |||||

| అధికార భాషలు | అరబ్బీ భాష, కుర్దిష్ | |||||

| ప్రజానామము | ఇరాకీ | |||||

| ప్రభుత్వం | అభివృద్ధి చెందుతున్న పార్లమెంటరీ గణతంత్రం | |||||

| - | అధ్యక్షుడు | జలాల్ తలబాని | ||||

| - | ప్రధాన మంత్రి | నూరి అల్ మాలికి | ||||

| స్వతంత్రం | ||||||

| - | from the ఉస్మానియా సామ్రాజ్యము | అక్టోబరు 1 1919 |

||||

| - | from the యునైటెడ్ కింగ్ డం | అక్టోబరు 3 1932 |

||||

| - | జలాలు (%) | 1.1 | ||||

| జనాభా | ||||||

| - | 2007 అంచనా | 29,267,0004 (39వది) | ||||

| జీడీపీ (PPP) | 2006 అంచనా | |||||

| - | మొత్తం | $89.8 బిలియన్లు (61వది) | ||||

| - | తలసరి | $2,900 (130th) | ||||

| కరెన్సీ | ఇరాకీ దీనార్ (IQD) |

|||||

| కాలాంశం | GMT+3 (UTC+3) | |||||

| - | వేసవి (DST) | not observed (UTC+3) | ||||

| ఇంటర్నెట్ డొమైన్ కోడ్ | .iq | |||||

| కాలింగ్ కోడ్ | +964 | |||||

| 1 | The Kurds use Ey Reqîb as the anthem. | |||||

| 2 | ఇరాకీ కుర్దిస్తాన్ రాజధాని అర్బీల్. | |||||

| 3 | Arabic and Kurdish are the official languages of the Iraqi government. According to Article 4, Section 4 of the ఇరాక్ రాజ్యాంగం, Assyrian (Syriac) (a dialect of Aramaic) and Iraqi Turkmen (a dialect of Southern Azerbaijani) languages are official in areas where the respective populations they constitute density of population. | |||||

| 4 | CIA World Factbook | |||||

ఇరాక్ (ఆంగ్లం : Iraq), అధికారికనామం రిపబ్లిక్ ఆఫ్ ఇరాక్ (అరబ్బీ : جمهورية العراق ), జమ్-హూరియత్ అల్-ఇరాక్, పశ్చిమ ఆసియా లోని ఒక సార్వభౌమ దేశం. దీని రాజధాని బాగ్దాదు. దేశం ఉత్తర సరిహద్దులో, టర్కీ తూర్పు సరిహద్దులో ఇరాన్, ఆగ్నేయ సరిహద్దులో కువైట్, దక్షిణ సరిహద్దులో సౌదీ అరేబియా, వాయవ్య సరిహద్దులో జోర్డాన్ పశ్చిమ సరిహద్దులో సిరియా దేశం ఉన్నాయి. ఇరాక్ దక్షిణ ప్రప్రాంతం అరేబియన్ ద్వీపకల్పంలో ఉంది. అతిపెద్ద నగరం మరియు దేశరాజధాని అయిన బాగ్దాదు నగరం దేశం మద్యభాగంలో ఉంటుంది. ఇరాక్లో అధికంగా అరేబియన్లు మరియు కుర్దీ ప్రజలు ఉన్నారు. తరువాత స్థానాలలో అస్సిరియన్, ఇరాకీ తుర్క్మెనీయులు, షబకీయులు, యజిదీలు, ఇరాకీ ఆర్మేనియన్లు, ఇరాకీ సిర్కాసియన్లు మరియు కవ్లియాలు ఉన్నారు.[1] ఇరాక్ లోని 36 మిలియన్ ప్రజలలో 95% సున్నీ ముస్లిములు ఉన్నారు.వీరుకాక దేశంలో క్రైస్తవం, యార్సన్, యజిదీయిజం మరియు మండీనిజం కూడా ఆచరణలో ఉంది. ఇరాక్లో 58 km (36 mi) పొడవైన సన్నని సముద్రతీర ప్రాంతం (పర్షియన్ గల్ఫ్ ఉత్తరంలో) ఉంది. ఈ ప్రాంతంలో సారవంతమైన టిగ్రిస్-యూఫ్రేట్స్ నదీ మైదానం ఉంది. ఇది జగ్రోస్ పర్వతశ్రేణికి వాయవ్యంలో సిరియన్ ఎడారికి తూర్పు భాగంలో ఉంది. [2] ఇరాక్లోని రెండు ప్రధాన నదులైన టిగ్రిస్ మరియు యూఫ్రేట్స్ నదులు దక్షిణంగా ప్రవహించి షాట్ అల్ అరబ్ వైపు ప్రవహించి పర్షియన్ గల్ఫ్లో సంగమిస్తాయి. ఈ నదులు ఇరాక్కు సారవంతమైన వ్యవసాయ భూమిని అందిస్తున్నాయి. టిగ్రిస్-యూఫ్రేట్స్ నదీప్రాంతాలకు మెసపటోమియా అని చారిత్రక నామం ఉంది. ఇక్కడ ఇది తరచుగా మానవ నాగరికతా సోపానంగా వర్ణించబడుతుంది.మానవనాగరికతలో వ్రాయడం, చదవడం మరియు చట్టం రూపకల్పన చక్కగా నిర్వహించబడిన ప్రభుత్వం పాలనలో నగరనిర్మాణం చేసి ప్రజలు నివసించారు.క్రీ.పూ 6 వ శతాబ్ధం నుండి ఈ ప్రాంతంలో పలు నాగరికతలు నిరంతర మ్ఘాఆ విజయవంతంగా విలసిల్లాయి. ఇరాక్ అకాడియన్, నియో - సుమేరియన్ సాంరాజ్యం, నియో అస్సిరియన్ మరియు నియో - బాబిలోనియన్ సాంరాజ్యాలు విలసిలాయి. ఇరాక్ మెడియన్ సాంరాజ్యం, అచమనిద్ అస్సిరియన్, సెల్యూసిడ్ సాంరాజ్యం, అర్ససిద్ సాంరాజ్యం, సస్సనిద్ సాంరాజ్యం, రోమన్ సాంరాజ్యం, రషిదున్ సాంరాజ్యం, సఫావిద్ సాంరాజ్యం, అఫ్షరిద్ రాజవంశ పాలన మరియు ఓట్టమన్ సాంరాజ్యాలలో భాగంగా ఉంది. అలాగే యునైటెడ్ కింగ్డం ఆధీనంలో కొంతకాలం ఉంది. [3]1920లో ఓట్టమన్ సాంరాజ్యం విభజన తరువాత ఇరాక్ సరిహద్దులు సరికొత్తగా నిర్ణయించబడ్డాయి. 1921లో కింగ్డం ఆఫ్ ఇరాక్ సాంరాజ్యం స్థాపించబడింది. 1932లో యునైటెడ్ కింగ్డం నుండి స్వతంత్రం లభించింది. 1958లో ఇరాక్ సాంరాజ్యం విచ్ఛిన్నమై ఇరాక్ రిపబ్లిక్ స్థాపించబడింది. 1968 నుండి 2003 వరకు బాత్ పార్టీ ఇరాక్ను పాలించింది.2003 లో యునైటెడ్ స్టేట్స్ ఇరాక్ మీద దాడి చేసింది. సదాం హుస్సేన్ ప్రభుత్వం తొలగించబడి ఇరాక్లో పార్లమెంటు ఎన్నికలు నిర్వహించబడ్డాయి. 2011 నుండి ఇరాక్ నుండి అమెరికన్ దళాలు వైదొలగాయి. [4] 2011-2013 వరకు ఇరాక్ విప్లవం కొనసాగింది. సిరియన్ అంతర్యుద్ధం ప్రభావం ఇరాక్ వరకు వ్యాపించింది..

పేరువెనుక చరిత్ర

6 వ శతాబ్ధం వరకు ఈ ప్రాంతానికి అరబిక్ పేరు العراق al-ʿIrāq వరకు వాడుకలో ఉండేది. ఈ పేరు వెనుక పలు కథనాలు ప్రచారంలో ఉన్నాయి. సుమేరియన్ నగరాలలో ఒకటైన ఉరుక్ (బైబిల్ పేరు ఎర్చ్) పేరుతో ఈప్రాంతం గుర్తించబడిందని భావిస్తున్నారు.[5][6]అరబిక్ జానపద వాడుకలో లోతుగా పాతుకున్న, చక్కగా జలసమృద్ధి కలిగిన, సారవంతమైన అని కూడా ఇరాక్ పదానికి అర్ధం అని భావించబడుతుంది. [7]మద్యయుగకాలంలో దిగువ మెసపటోమియా ప్రాంతం ఇరాకియన్ అరబి మరియు పర్షియన్ ఇరాక్ (విదేశీ ఇరాక్) అని పిలువబడింది.[8] [9][10] ప్రారంభ ఇస్లామిక్ వాడుకలో సారవంతమైన భూమిని (టిగ్రిస్ మరియు యూఫ్రేట్స్ సారవంతమైన భూమిని ) సవాద్ అంటారు. అరబిక్ పదం عراق అంటే అంచు, తీరం మరియు కొన అని అర్ధం. గ్రామీణ భాషలో ఏటవాలు ప్రాంతం అని అర్ధం. అల్- జజిరా (మెసపటోమియా) మైదానం అల్- ఇరాక్ అరబి ఉత్తర పశ్చిమ తీరంలో ఉంది. [11].

History

Pre-historic era

Between 65,000 BC and 35,000 BC northern Iraq was home to a Neanderthal culture, archaeological remains of which have been discovered at Shanidar Cave[12] This same region is also the location of a number of pre-Neolithic cemeteries, dating from approximately 11,000 BC.[13]

Since approximately 10,000 BC, Iraq (alongside Asia Minor and The Levant) was one of centres of a Caucasoid Neolithic culture (known as Pre-Pottery Neolithic A) where agriculture and cattle breeding appeared for the first time in the world. The following Neolithic period (PPNB) is represented by rectangular houses. At the time of the pre-pottery Neolithic, people used vessels made of stone, gypsum and burnt lime (Vaisselle blanche). Finds of obsidian tools from Anatolia are evidences of early trade relations.

Further important sites of human advancement were Jarmo (circa 7100 BC),[13] the Halaf culture and Ubaid period (between 6500 BC and 3800 BC),[14] these periods show ever increasing levels of advancement in agriculture, tool making and architecture.

Ancient Iraq

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (June 2014) |

The historical period in Iraq truly begins during the Uruk period (4000 BC to 3100 BC), with the founding of a number of Sumerian cities, and the use of Pictographs, Cylinder seals and mass-produced goods.[16]

The "Cradle of Civilization" is thus a common term for the area comprising modern Iraq as it was home to the earliest known civilisation, the Sumerian civilisation, which arose in the fertile Tigris-Euphrates river valley of southern Iraq in the Chalcolithic (Ubaid period).

It was here in the late 4th millennium BC, that the world's first writing system and recorded history itself were born. The Sumerians were also the first to harness the wheel and create City States, and whose writings record the first evidence of Mathematics, Astronomy, Astrology, Written Law, Medicine and Organised religion.

The Sumerians spoke a Language Isolate, in other words, a language utterly unrelated to any other, including the Semitic Languages, Indo-European Languages, Afroasiatic languages or any other isolates. The major city states of the early Sumerian period were; Eridu, Bad-tibira, Larsa, Sippar, Shuruppak, Uruk, Kish, Ur, Nippur, Lagash, Girsu, Umma, Hamazi, Adab, Mari, Isin, Kutha, Der and Akshak.

Cities such as Ashur, Arbela (modern Irbil) and Arrapkha (modern Kirkuk) were also extant in what was to be called Assyria from the 25th century BC, however at this early stage they were Sumerian ruled administrative centres.

In the 26th century BC, Eannatum of Lagash created what was perhaps the first Empire in history, though this was short lived. Later, Lugal-Zage-Si, the priest-king of Umma, overthrew the primacy of the Lagash dynasty in the area, then conquered Uruk, making it his capital, and claimed an empire extending from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean.[17] It was during this period that the Epic of Gilgamesh originates, which includes the tale of The Great Flood.

From approximately 3000 BC, a Semitic people had also entered Iraq from the west and settled amongst the Sumerians. These people spoke an East Semitic language which would later come to be known as Akkadian. From the 29th century BC Akkadian Semitic names began to appear on king lists and administrative documents of various city states.

During the 3rd millennium BCE a cultural symbiosis developed between the Sumerians and the Akkadians, which included widespread bilingualism. The influences between Sumerian and Akkadian are evident in all areas including lexical borrowing on a massive scale—and syntactic, morphological, and phonological convergence. This mutual influence has prompted scholars to refer to Sumerian and Akkadian of the 3rd millennium BCE as a Sprachbund.[18] From this period the civilisation in Iraq came to be known as Sumero-Akkadian.

Between the 29th and 24th centuries BC, a number of kingdoms and city states within Iraq began to have Akkadian speaking dynasties; including Assyria, Ekallatum, Isin and Larsa.

However, the Sumerians remained generally dominant until the rise of the Akkadian Empire (2335-2124 BC), based in the city of Akkad in central Iraq. Sargon of Akkad, originally a Rabshakeh to a Sumerian king, founded the empire, he conquered all of the city states of southern and central Iraq, and subjugated the kings of Assyria, thus uniting the Sumerians and Akkadians in one state. He then set about expanding his empire, conquering Gutium, Elam, Cissia and Turukku in Ancient Iran, the Hurrians, Luwians and Hattians of Anatolia, and the Amorites and Eblaites of Ancient Syria.

After the collapse of the Akkadian Empire in the late 22nd century BC, the Gutians occupied the south for a few decades, while Assyria reasserted its independence in the north. This was followed by a Sumerian renaissance in the form of the Neo-Sumerian Empire. The Sumerians under king Shulgi conquered almost all of Iraq except the northern reaches of Assyria, and asserted themselves over the Elamites, Gutians and Amorites.

An Elamite invasion in 2004 BC brought the Sumerian revival to an end. By the mid 21st century BC the Akkadian speaking kingdom of Assyria, had risen to dominance in northern Iraq, it expanded territorially into the north eastern Levant, central Iraq, and eastern Anatolia, forming the Old Assyrian Empire (circa 2035-1750 BC) under kings such as Puzur-Ashur I, Sargon I, Ilushuma and Erishum I, the latter of whom produced the most detailed set of Written Laws yet written. The south broke up into a number of Akkadian speaking states, Isin, Larsa and Eshnunna being the major ones.

During the 20th century BC, the Canaanite speaking Northwest Semitic Amorites began to migrate into southern Mesopotamia. Eventually these Amorites began to set up small petty kingdoms in the south, as well as usurping the thrones of extant city states such as Isin, Larsa and Eshnunna.

One of these small kingdoms founded in 1894 BC contained the then small administrative town of Babylon within its borders. It remained insignificant for over a century, overshadowed by older and more powerful states such as Assyria, Elam, Isin, Ehnunna and Larsa.

In 1792 BC, an Amorite ruler named Hammurabi came to power in this state, and immediately set about building Babylon from a minor town into a major city, declaring himself its king. Hammurabi conquered the whole of southern and central Iraq, as well as Elam to the east and Mari to the west, then engaged in a protracted war with the Assyrian king Ishme-Dagan for domination of the region, creating the short lived Babylonian Empire. He eventually prevailed over the successor of Ishme-Dagan and subjected Assyria and its Anatolian colonies.

It is from the period of Hammurabi that southern Iraq came to be known as Babylonia, while the north had already coalesced into Assyria hundreds of years before. However, his empire was short lived, and rapidly collapsed after his death, with both Assyria and southern Iraq, in the form of the Sealand Dynasty, falling back into native Akkadian hands. The foreign Amorites clung on to power in a once more weak and small Babylonia until it was sacked by the Indo-European speaking Hittite Empire based in Anatolia in 1595 BC. After this, another foreign people, the Language Isolate speaking Kassites, originating in the Zagros Mountains of Ancient Iran, seized control of Babylonia, where they were to rule for almost six hundred years, by far the longest dynasty ever to rule in Babylon.

Iraq was from this point divided into three polities; Assyria in the north, Kassite Babylonia in the south central region, and the Sealand Dynasty in the far south. The Sealand Dynasty was finally conquered into Babylonia by the Kassites circa 1380 BC.

The Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1020 BC) saw Assyria rise to be the most powerful nation in the known world. Beginning with the campaigns of Ashur-uballit I, Assyria destroyed the rival Hurrian-Mitanni Empire, annexed huge swathes of the Hittite Empire for itself, annexed northern Babylonia from the Kassites, forced the Egyptian Empire from the region, and defeated the Elamites, Phrygians, Canaanites, Phoenicians, Cilicians, Gutians, Dilmunites and Arameans. At its height the Middle Assyrian Empire stretched from The Caucasus to Dilmun (modern Bahrain), and from the Mediterranean coasts of Phoenicia to the Zagros Mountains of Iran. In 1235 BC, Tukulti-Ninurta I of Assyria took the throne of Babylon, thus becoming the very first native Mesopotamian to rule the state.

During the Bronze Age collapse (1200-900 BC) Babylonia was in a state of chaos, dominated for long periods by Assyria and Elam. The Kassites were driven from power by Assyria and Elam, allowing native south Mesopotamian kings to rule Babylonia for the first time, although often subject to Assyrian or Elamite rulers. However, these East Semitic Akkadian kings, were unable to prevent new waves of West Semitic migrants entering southern Iraq, and during the 11th century BC Arameans and Suteans entered Babylonia from The Levant, and these were followed in the late 10th to early 9th century BC by the migrant Chaldeans who were closely related to the earlier Arameans.

After a period of comparative decline in Assyria, it once more began to expand with the Neo Assyrian Empire (935–605 BC). This was to be the largest and most powerful empire the world had yet seen, and under rulers such as Adad-Nirari II, Ashurnasirpal, Shalmaneser III, Semiramis, Tiglath-pileser III, Sargon II, Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal, Iraq became the centre of an empire stretching from Persia, Parthia and Elam in the east, to Cyprus and Antioch in the west, and from The Caucasus in the north to Egypt, Nubia and Arabia in the south.

The Arabs are first mentioned in written history (circa 850 BC) as a subject people of Shalmaneser III, dwelling in the Arabian Peninsula. The Chaldeans are first mentioned at this time also.

It was during this period that an Akkadian influenced form of Eastern Aramaic was introduced by the Assyrians as the lingua franca of their vast empire, and Mesopotamian Aramaic began to supplant Akkadian as the spoken language of the general populace of both Assyria and Babylonia. The descendant dialects of this tongue survive amongst the Assyrians of northern Iraq to this day.

In the late 7th century BC the Assyrian Empire tore itself apart with a series of brutal civil wars, weakening itself to such a degree that a coalition of its former subjects; the Babylonians, Chaldeans, Medes, Persians, Parthians, Scythians and Cimmerians, were able to attack Assyria, finally bringing its empire down by 605 BC.[19]

The short lived Neo-Babylonian Empire (620-539 BC) succeeded that of Assyria. It failed to attain the size, power or longevity of its predecessor, however it came to dominate The Levant, Canaan, Arabia, Israel and Judah, and to defeat Egypt. Initially, Babylon was ruled by yet another foreign dynasty, that of the Chaldeans, who had migrated to the region in the late 10th or early 9th century BC. Its greatest king, Nebuchadnezzar II rivalled another non native ruler, the ethnically unrelated Amorite king Hammurabi, as the greatest king of Babylon. However, by 556 BC the Chaldeans had been deposed from power by the Assyrian born Nabonidus and his son and regent Belshazzar.